Geometric Distances: A Crash Course

Published:

In a previous blog post I introduced the concepts of standardization and normalization. A concept common to both of those techniques is distance. Simply put, distance is a mathematical summary of the differences between two objects. These objects can be data points or they can be full distributions. Distance measures fall into two categories:

Geometric Distances: Measure of similiartity between vectors based on the distance between them in multidimensional space.

Statistical Distances: Distance between statistical objects denoting similarity between them.

As the title of this post indicates, this post will focus on geometric distances. For most people, the concept of geometric distance is pretty easy to grasp as it is the one most similar to how we think about distance in the physical world. The common perception of distance is the length of the space between two points, such as one’s home and the grocery store. We either think of these distances as being direct, or as having to traverse streets or sidewalks that may require multiple turns. With these ideas in mind, let’s take a look at three common geometric distance measures: Euclidean Distance, Manhattan Distance, and Cosine Distance.

Euclidean Distance

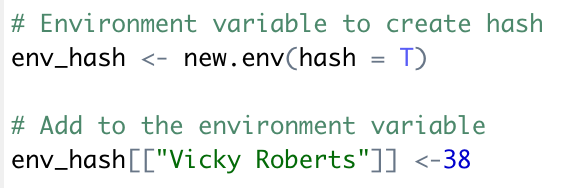

Euclidean distance is the direct (shortest) distance between two points. Of all the geometric distance measures this is the easiest to understand. Also, as long as you passed high school geometry you already know how to calculate it as it is the square root of the Pythagorean Theorem. Imagine in this scenario that you have two points, A and B. A can be identifed at coordinates $(x_{A}, y_{A})$ and B can be identified at coordinates $(x_{B}, y_{B})$. The relevant equation for Euclidean distance then becomes as follows:

\[d(A,B) = \sqrt{A^{2} + B^{2}}\]Using the equation above with points A and B, imagine a right triangle with a 90-degree angle at point C.

When to Use It: Clustering algorithms for normally distributed data, such as K-Means.

Manhattan Distance

The Manhattan Distance is also very easy to grasp as it is analogous to movement in the real world. Think of it like walking in a city. Instead of walking directly from your starting point to your destination as you would with Euclidean Distance, with Manhattan Distance you have to walk straight in one direction. Then, imagine you turn a corner to go in another direction. For each stretch you walk between two points, such as your starting point and the first turn you make, and then from the first turn to any following point, you calculate the distance of that stretch. At the end, you sum together each stretch of distance for the overall distance measure.

\[d(A,B) = |x_{A} - x_{B}| + |y_{A} - y_{B}|\]As before, imagine two points A and B.

When to Use It: Regression analyses.

Cosine Distance

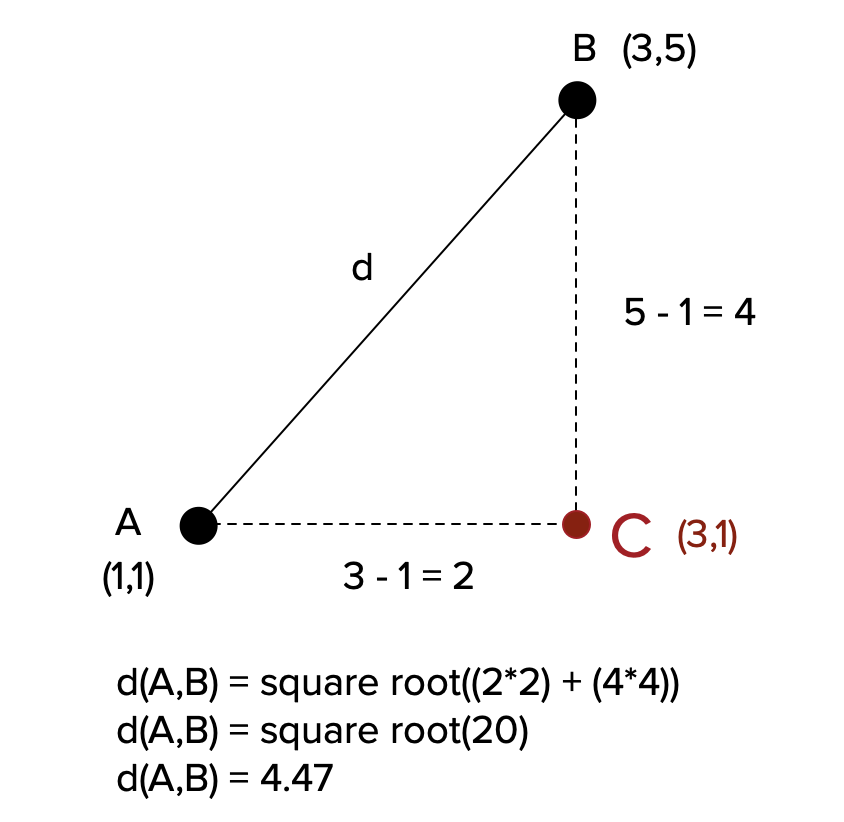

Of the three geometric distances presented in this post, cosine distance has the most complex calculation but is still easy to conceptualize. Think again about two points. The cosine distance is the cosine of the angle between them, where the angle is measured from some origin point. This makes for some fairly easy ways to judge distance. - Cosine of 0 deg = 1, similar - Cosine of 90 deg = 0, dissimilar

The formula can be fairly complicated, so let’s take a moment to break it down. Its initial form is below:

\[d(A,B) = 1 - \frac{A \cdot B}{||A|| * ||B||}\]The numerator refers to the dot product, so \(\sum_{i = 1}^{n} A_{i} * B_{i}\)

The denominator refers to the cross product of A and B, so \(\sqrt{\sum_{i = 1}^n A_{i}^2} * \sqrt{\sum_{i = 1}^n B_{i}^2}\)

Each component may seem complicated, but if you know how to factor radicals it simplifies as you see below:

When to Use It: Judging similarity of documents for text analyses.

While this is by no means an exhaustive list of geometric distances, these are the ones I most commonly use. Also, I think these are the ones that offer the gentlest introduction to the concept of geometric distances. In a future post I will deepen the discussion of distance by talking about statistical distance.